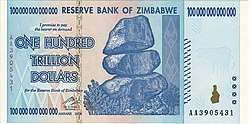

100 Trilyun Dolar Zimbabwe = US$ 5 (Rp 45.000)!

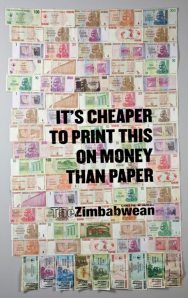

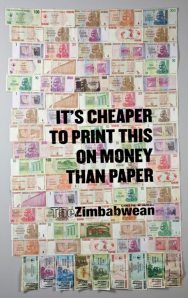

Uang Kertas 100 trilyun dolar Zimbabwe nilainya cuma US$ 5 (Rp 45.000)! Orang harus bawa setumpuk uang untuk belanja sehari2. Ini pemiskinan massal. Kezaliman thd rakyat!

“…Allah Tahu, sedang kamu tidak tahu!” [Al Baqarah 216]

Tahun 90-an ongkos naik bis cuma Rp 100. Tahun 2000-an jadi Rp 2000. 10 tahun saja naik 20x lipat. Padahal gaji pada kurun itu belum tentu naiknya segitu. Jadi uang kertas itu pemiskinan massal. Padahal kalau digaji misalnya dgn 10 gram emas, niscaya dari 1400 tahun lalu hingga sekarang, meski jumlahnya tak berubah, nilainya juga tidak turun.

Allah dan RasulNya sudah memberi contoh pemakaian emas dan perak sebagai uang. Bukan uang kertas yang tiap tahun nilainya selalu turun dan sering terkena Krisis Keuangan.

Emas dan Perak karena punya nilai riel dibanding kertas, lebih stabil dan lebih tahan terhadap inflasi. Contohnya, 1 dinar (4,25 gram emas 22 karat) pada zaman Nabi bisa dipakai untuk membeli 1-2 ekor kambing. Ada satu hadits yang merupakan bukti sejarah stabilitas uang dinar di Hadits Riwayat Bukhari sebagai berikut:

”Ali bin Abdullah menceritakan kepada kami, Sufyan menceritakan kepada kami, Syahib bin Gharqadah menceritakan kepada kami, ia berkata, “Saya mendengar penduduk bercerita tentang ’Urwah, bahwa Nabi saw. memberikan uang satu Dinar kepadanya agar dibelikan seekor kambing untuk beliau, lalu dengan uang tersebut ia membeli dua ekor kambing, kemudian ia jual satu ekor dengan harga satu Dinar. Ia pulang membawa satu Dinar dan satu ekor kambing. Nabi saw. mendoakannya dengan keberkatan dalam jual belinya. Seandainya ‘Urwah membeli tanahpun, ia pasti beruntung.” (H.R.Bukhari)

Saat ini pun dengan

kurs 1 dinar=Rp 2,2 juta, kita bisa mendapat 1 kambing besar atau 2 ekor kambing kecil. Stabil bukan?

Hiperinflasi adalah penyakit umum dari Uang Kertas Fiat (uang yang tidak dijamin emas, perak, dan barang2 berharga lainnya). Banyak krisis keuangan terjadi di dunia termasuk di AS, Yunani, Turki, Indonesia, Zimbabwe, dsb karena uang kertas yang mereka pakai sebetulnya tidak berharga.

Foto di atas orang Jerman memakai uang sebagai wallpaper di tahun 1923. Ini karena nilainya sudah hampir tidak ada harganya karena hiperinflasi.

Gambar di atas menunjukkan turunnya nilai uang kertas Jerman Reich Mark. 1 Januari 2018 1 gram emas bisa dibeli dengan 3 Reich Mark. Pada 30 November 1923 (kurang dari 6 tahun) 1 gram emas nilainya sudah 3.000.000.000.000 Reich Mark. Uang Jerman turun hingga 1/1 trilyun hanya dalam waktu kurang dari 6 tahun! Sementara nilai emas stabil.

Gambar di atas menunjukkan bagaimana uang kertas Hongaria akhirnya jadi sampah tak berharga yang harus dibuang di jalan pada tahun 1946. Nilai terbesar pada uang kertas adalah 100 quintillion pengo pada tahun 1946 oleh Bank Nasional Hongaria. Nilainya 100.000.000.000.000.000.000). Tapi disingkat jadi 1.000.000.000 b-pengo.

Pasca Perang Dunia II, Hongaria mencatat inflasi bulanan tertinggi: 41.900.000.000.000.000% (4.19 × 1016% or 41.9 quadrillion percent) pada bulan Juli 1946. Harga naik 2 x lipat setiap 15,3 jam.

Foto di atas menunjukkan karena inflasi, akhirnya orang memakai gerobak untuk membawa uang kertasnya.

Sementara Zimbabwe per 14 November 2008 inflasi tahunannya mencapai 89,7

sextillion (10

21) percent. Inflasinya per bulan 5473%. Harga naik 2x lipat setiap 5 hari.

Bayangkan. Harga barang bisa naik 2 x lipat setiap 15,3 jam. Padahal gaji kita belum tentu naik sebesar itu. Jadi uang kertas sesungguhnya memiskinkan rakyat.

Hanya segelintir orang yang punya akses untuk mencetak uang atau membungakan uang saja yang bisa menikmati keuntungan.

Cara pemerintah menutupi inflasi adalah dengan melakukan redenominasi/revaluasi. Misalnya Turki merevaluasi Lira pada 1 Januari 2005 sehingga 1.000.000 Lira Lama (Turkish Lira-TRL) diganti dengan 1 Lira Turki Baru (TRY).

Di Indonesia tahun 1959 pada Zaman Soekarno pernah terjadi Sanering yang bukan hanya memangkas bilangan angka pada uang, tapi juga nilainya sehingga daya beli rakyat hancur. Yang jelas uang kertas yang tidak ada harganya tersebut banyak menimbulkan penderitaan pada rakyat.

Itulah sebabnya mengapa Allah memakai emas dan perak sebagai Nishab Zakat.

“…Allah Tahu, sedang kamu tidak tahu!” [Al Baqarah 216]

Referensi:

Hyperinflation and the currency

As noted, in countries experiencing hyperinflation, the

central bank often prints money in larger and larger denominations as the smaller denomination notes become worthless. This can result in the production of some interesting

banknotes, including those denominated in amounts of 1,000,000,000 or more.

- By late 1923, the Weimar Republic of Germany was issuing two-trillion Mark banknotes and postage stamps with a face value of fifty billion Mark. The highest value banknote issued by the Weimar government’s Reichsbank had a face value of 100 trillion Mark (100,000,000,000,000; 100 million million).[13][14] At the height of the inflation, one US dollar was worth 4 trillion German marks. One of the firms printing these notes submitted an invoice for the work to the Reichsbank for 32,776,899,763,734,490,417.05 (3.28 × 1019, or 33quintillion) Marks.[15]

- The largest denomination banknote ever officially issued for circulation was in 1946 by the Hungarian National Bank for the amount of 100 quintillion pengő (100,000,000,000,000,000,000, or 1020; 100 million million million) image. (There was even a banknote worth 10 times more, i.e. 1021 pengő, printed, but not issued image.) The banknotes however did not depict the numbers, “hundred million b.-pengő” (“hundred million trillion pengő”) and “one milliard b.-pengő” were spelled out instead. This makes the 100,000,000,000,000 Zimbabwean dollar banknotes the note with the greatest number of zeros shown.

- The Post-World War II hyperinflation of Hungary held the record for the most extreme monthly inflation rate ever — 41,900,000,000,000,000% (4.19 × 1016% or 41.9 quadrillion percent) for July, 1946, amounting to prices doubling every 15.3 hours. By comparison, recent figures (as of 14 November 2008) estimate Zimbabwe’s annual inflation rate at 89.7 sextillion (1021) percent.,[16] which corresponds to a monthly rate of 5473%, and a doubling time of about five days. In figures, that is 89,700,000,000,000,000,000,000%.

One way to avoid the use of large numbers is by declaring a new unit of currency (an example being, instead of 10,000,000,000 Dollars, a bank might set 1 new dollar = 1,000,000,000 old dollars, so the new note would read “10 new dollars.”) An example of this would be Turkey’s revaluation of the

Lira on 1 January 2005, when the old

Turkish lira (TRL) was converted to the

New Turkish lira (TRY) at a rate of 1,000,000 old to 1 new Turkish Lira. While this does not lessen the actual value of a currency, it is called

redenomination or

revaluation and also happens over time in countries with standard inflation levels. During hyperinflation, currency inflation happens so quickly that bills reach large numbers before revaluation.

Some banknotes were stamped to indicate changes of denomination. This is because it would take too long to print new notes. By the time new notes were printed, they would be obsolete (that is, they would be of too low a denomination to be useful).

Metallic coins were rapid casualties of hyperinflation, as the scrap value of metal enormously exceeded the face value. Massive amounts of coinage were melted down, usually illicitly, and exported for hard currency.

Governments will often try to disguise the true rate of inflation through a variety of techniques. None of these actions addresses the root causes of inflation and they, if discovered, tend to further undermine trust in the currency, causing further increases in inflation.

Price controlswill generally result in shortages and hoarding and extremely high demand for the controlled goods, resulting in disruptions of

supply chains. Products available to consumers may diminish or disappear as businesses no longer find it sufficiently profitable (or may be operating at a loss) to continue producing and/or distributing such goods at the legal prices, further exacerbating the shortages.

Examples of hyperinflation

Angola

Angola experienced hyperinflation from 1991 to 1995. It was a result of exchange restrictions following the introduction of the novo kwanza (

AON) to replace the original

kwanza (AOK) in 1990. At the first months of 1991, the highest denomination was 50 000 AON. By 1994, the highest denomination was 500 000 kwanzas. In the 1995 currency reform, the readjusted kwanza (AOR) replaced the novo kwanza at the ratio of 1 000 AON to 1 AOR, but hyperinflation continued as further denominations of up to 5 000 000 AOR were issued. In the 1999 currency reform, the kwanza (AOA) was reintroduced at the ratio of 1 million AOR to 1 AOA. Currently, the highest denomination banknote is 2 000 AOA and the overall impact of hyperinflation was 1 AOA = 1 billion AOK.

Argentina

Argentina went through steady inflation from 1975 to 1991. At the beginning of 1975, the highest denomination was 1,000

pesos. In late 1976, the highest denomination was 5,000 pesos. In early 1979, the highest denomination was 10,000 pesos. By the end of 1981, the highest denomination was 1,000,000 pesos. In the 1983 currency reform, 1 peso argentino was exchanged for 10,000 pesos. In the 1985 currency reform, 1 austral was exchanged for 1,000 pesos argentinos. In the 1992 currency reform, 1 new peso was exchanged for 10,000 australes. The overall impact of hyperinflation: 1 (1992) peso = 100,000,000,000 pre-1983 pesos.

Criticism of the official view

Ellen Brown, author of Web of Debt, admits that the left-oriented policy that Argentina had had since 1947, when

Juan Peron came to power, did actually create inflation. But the inflation did not become a national crisis until during the eight years that followed Peron’s death in 1974. During these years the inflation rose to 206 percent, due to a “deliberate radical devaluation of the currency of the new government, along with a 175 percent increase in oil prices”. This devaluation was, as she sees it, done with the hidden purpose of destabilizing the economy (to create a chaos). And it was, in any case, not caused by a sudden and massive increase in the printing of money by the government. She also cites Professor Escudé who writes that this devaluation led both to “the astronomical high inflation” and “to the spread of a speculative financial system that became a hallmark of Argentina’s financial life”.

[citation needed]

Austria

In 1922, inflation in Austria reached 1426%, and from 1914 to January 1923, the consumer price index rose by a factor of 11836, with the highest banknote in denominations of 500,000

krones.

[17]

Belarus

Belarus experienced steady inflation from 1994 to 2002. In 1993, the highest denomination was 5,000

rublei. By 1999, it was 5,000,000 rublei. In the 2000 currency reform, the ruble was replaced by the new ruble at an exchange rate of 1 new ruble = 1,000 old rublei. The highest denomination in 2008 was 100,000 rublei, equal to 100,000,000 pre-2000 rublei.

Bolivia

Bolivia experienced its worst inflation between 1984 and 1986. Before 1984, the highest denomination was 1,000

pesos bolivianos. By 1985, the highest denomination was 10 Million pesos bolivianos. In 1985, a Bolivian note for 1 million pesos was worth 55 cents in US dollars, one-thousandth of its exchange value of $5,000 less than three years previously.

[18] In the 1987 currency reform, the Peso Boliviano was replaced by the

Boliviano at a rate of 1,000,000 : 1.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina went through its worst inflation in 1993. In 1992, the highest denomination was 1,000

dinara. By 1993, the highest denomination was 100,000,000 dinara. In the

Republika Srpska, the highest denomination was 10,000 dinara in 1992 and 10,000,000,000 dinara in 1993. 50,000,000,000 dinara notes were also printed in 1993 but never issued.

Brazil

From 1967–1994, the base currency unit was shifted seven times to adjust for inflation in the final years of the

Brazilian military dictatorshipera. A 1967

cruzeiro was, in 1994, worth less than one trillionth of a US cent, after adjusting for multiple devaluations and note changes. In that same year, inflation reached a record 2,075.8%. A new currency called

real was adopted in 1994, and hyperinflation was eventually brought under control.

[19] The

real was also the currency in use until 1942; 1 (current) real is the equivalent of 2,750,000,000,000,000,000 of Brazil’s first currency (called

réis in Portuguese).

Bulgaria

In 1996, the Bulgarian economy collapsed due to the slow and mismanaged economic reforms of several governments in a row, shortages of wheat, and an unstable and decentralized banking system, which led to an inflation rate of 311% and the collapse of the

lev, with the exchange rate to dollars reaching 3000. When pro-reform forces came into power in the spring 1997, an ambitious economic reform package, including introduction of a currency board regime and pegging the Bulgarian Lev to the German Deutsche Mark (and consequently to the euro), was agreed to with the

International Monetary Fund and the

World Bank, and the economy began to stabilize.

China

As the first user of

fiat currency, China has had an early history of troubles caused by hyperinflation. The

Yuan Dynasty printed huge amounts of fiat paper money to fund their wars, and the resulting hyperinflation, coupled with other factors, led to its demise at the hands of a revolution. The Republic of China went through the worst inflation 1948–49. In 1947, the highest denomination was 50,000

yuan. By mid-1948, the highest denomination was 180,000,000 yuan. The 1948 currency reform replaced the yuan by the gold yuan at an exchange rate of 1 gold yuan = 3,000,000 yuan. In less than a year, the highest denomination was 10,000,000 gold yuan. In the final days of the civil war, the Silver Yuan was briefly introduced at the rate of 500,000,000 Gold Yuan. Meanwhile the highest denomination issued by a regional bank was 6,000,000,000 yuan (issued by Xinjiang Provincial Bank in 1949). After the

renminbi was instituted by the new communist government, hyperinflation ceased with a revaluation of 1:10,000 old

Renminbi in 1955. The overall impact of inflation was 1 Renminbi = 15,000,000,000,000,000,000 pre-1948 yuan.

Free City of Danzig

Danzig went through its worst inflation in 1923. In 1922, the highest denomination was 1,000

Mark. By 1923, the highest denomination was 10,000,000,000 Mark.

Georgia

Georgia went through its worst inflation in 1994. In 1993, the highest denomination was 100,000 coupons [kuponi]. By 1994, the highest denomination was 1,000,000 coupons. In the 1995 currency reform, a new currency, the

lari, was introduced with 1 lari exchanged for 1,000,000 coupons.

Germany

Germany went through its worst inflation in 1923. In 1922, the highest denomination was 50,000

Mark. By 1923, the highest denomination was 100,000,000,000,000 Mark. In December 1923 the exchange rate was 4,200,000,000,000 Marks to 1 US dollar.

[20] In 1923, the rate of inflation hit 3.25 × 10

6 percent per month (prices double every two days). Beginning on 20 November 1923, 1,000,000,000,000 old Marks were exchanged for 1

Rentenmark so that 4.2 Rentenmarks were worth 1 US dollar, exactly the same rate the Mark had in 1914.

[20]

Greece

Greece went through its worst inflation in 1944. In 1942, the highest denomination was 50,000

drachmai. By 1944, the highest denomination was 100,000,000,000 drachmai. In the 1944 currency reform, 1 new drachma was exchanged for 50,000,000,000 drachmai. Another currency reform in 1953 replaced the drachma at an exchange rate of 1 new drachma = 1,000 old drachmai. The overall impact of hyperinflation: 1 (1953) drachma = 50,000,000,000,000 pre 1944 drachmai. The Greek monthly inflation rate reached 8.5 billion percent in October 1944.

Hungary, 1922–24

The

Treaty of Trianon and political instability between 1919 and 1924 led to a major inflation of Hungary’s currency. Unable to tax adequately, the government resorted to printing money and by 1922 inflation in Hungary had reached 98% per month.

The 100 million b.-pengő note was the highest denomination of banknote ever issued, worth 10

20or 100 quintillion

Hungarian pengő (1946).

Hungary, 1945–46

Hungary went through the worst inflation ever recorded between the end of 1945 and July 1946. In 1944, the highest denomination was 1,000

pengő. By the end of 1945, it was 10,000,000 pengő. The highest denomination in mid-1946 was 100,000,000,000,000,000,000 pengő. A special currency the adópengő – or tax pengő – was created for tax and postal payments.

[21] The value of the adópengő was adjusted each day, by radio announcement. On 1 January 1946 one adópengő equaled one pengő. By late July, one adópengő equaled 2,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 or 2×10

21 pengő. When the pengő was replaced in August 1946 by the

forint, the total value of all Hungarian banknotes in circulation amounted to

1/

1,000 of one US dollar.

[22] It is the most severe known incident of inflation recorded, peaking at 1.3 × 10

16 percent per month (prices double every 15 hours).

[23] The overall impact of hyperinflation: On 18 August 1946, 400,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 or 4×10

29 (four hundred

octillion (

short scale)) pengő became 1 forint.

Some historians believe

[24][unreliable source?] that this hyperinflation was purposely started by trained Russian Marxists in order to destroy the Hungarian middle and upper classes.

Israel

Inflation accelerated in the 1970s, rising steadily from 13% in 1971 to 111% in 1979. From 133% in 1980, it leaped to 191% in 1983 and then to 445% in 1984, threatening to become a four-digit figure within a year or two. In 1985 Israel froze most prices by law

[citation needed] and enacted other measures as part of

an economic stabilization plan. That same year, inflation more than halved, to 185%. Within a few months, the authorities began to lift the price freeze on some items; in other cases it took almost a year. By 1986, inflation was down to 19%.

Krajina

The

Republic of Serbian Krajina went through its worst inflation in 1993. In 1992, the highest denomination was 50,000

dinara. By 1993, the highest denomination was 50,000,000,000 dinara. Note that this unrecognized country was reincorporated into Croatia in 1995.

Mexico

In spite of the Oil Crisis of the late 1970s (Mexico is a producer and exporter), and due to excessive social spending, Mexico defaulted on its external debt in 1982. As a result, the country suffered a severe case of capital flight and several years of hyperinflation and

peso devaluation. On 1 January 1993, Mexico created a new currency, the nuevo peso (“new peso”, or MXN), which chopped 3 zeros off the old peso, an inflation rate of 10,000% over the several years of the crisis. (One new peso was equal to 1000 of the obsolete MXP pesos).

North Korea, 1947–2009

Though the

North Korean Won never technically failed, and is still the official currency of the reclusive communist nation, a 2009 revaluation showed the rest of the world rare cracks in the monolithic image Pyongyang presents. The government gave citizens seven days to turn in their old won for new won – with 1,000 of the old worth 10 of the new – but allowed a maximum exchange of 150,000 of the old won. That means each adult can exchange about US$740-worth of won. The revaluation and exchange cap wiped out the savings of many North Koreans, and reportedly caused unrest in parts of the country. According to a September 2009

BBC report, some department stores in Pyongyang even stopped accepting North Korean won, instead insisting upon payment in U.S. Dollars, Chinese Yuan, Euros, or even Japanese Yen.

Nicaragua

Nicaragua went through the worst inflation from 1987 to 1990. From 1943 to April 1971, one US dollar equalled 7

córdobas. From April 1971-early 1978, one US dollar was worth 10 córdobas. In early 1986, the highest denomination was 10,000 córdobas. By 1987, it was 1,000,000 córdobas. In the 1988 currency reform, 1 new córdoba was exchanged for 10,000 old córdobas. The highest denomination in 1990 was 100,000,000 new córdobas. In the 1991 currency reform, 1 new córdoba was exchanged for 5,000,000 old córdobas. The overall impact of hyperinflation: 1 (1991) córdoba = 50,000,000,000 pre-1988 córdobas.

Peru

Peru experienced its worst inflation from 1988–1990. In the 1985 currency reform, 1 inti was exchanged for 1,000

soles. In 1986, the highest denomination was 1,000 intis. But in September 1988, monthly inflation went to 132%. In August 1990, monthly inflation was 397%. The highest denomination was 5,000,000 intis by 1991. In the 1991 currency reform, 1 nuevo sol was exchanged for 1,000,000 intis. The overall impact of hyperinflation: 1 nuevo sol = 1,000,000,000 (old) soles.

Philippines

The Japanese government occupying the Philippines during the

World War II issued fiat currencies for general circulation. The Japanese-sponsored

Second Philippine Republic government led by

Jose P. Laurel at the same time outlawed possession of other currencies, most especially “guerilla money.” The fiat money was dubbed “Mickey Mouse Money” because it is similar to play money and is next to worthless. Survivors of the war often tell tales of bringing suitcase or

bayong (native bags made of woven coconut or

buri leaf strips) overflowing with Japanese-issued bills. In the early times, 75 Mickey Mouse

pesos could buy one duck egg.

[25] In 1944, a box of matches cost more than 100 Mickey Mouse pesos.

[26]

In 1942, the highest denomination available was 10 pesos. Before the end of the war, because of inflation, the Japanese government was forced to issue 100, 500 and 1000 peso notes.

Poland, 1921–1924

After Poland’s independence in 1918, the country soon began experiencing extreme inflation. By 1921, prices had already risen 251 times above those of 1914, but in the following three years they rose by 988,223%

[27] with a peak rate in late 1923 of prices doubling every nineteen and a half days.

[28] At independence there was 8

marek per US dollar, but by 1923 the exchange rate was 6,375,000 marek (mkp) for 1 US dollar. The highest denomination was 10,000,000 mkp. In the 1924 currency reform there was a new currency introduced: 1

zloty = 1,800,000 mkp.

Poland, 1989–1991

Poland experienced a second hyperinflation between 1989 and 1991. The highest denomination in 1989 was 200,000

zlotych. It was 1,000,000 zlotych in 1991 and 2,000,000 zlotych in 1992; the exchange rate was 9500 zlotych for 1 US dollar in January 1990 and 19600 zlotych at the end of August 1992. In the 1994 currency reform, 1 new zloty was exchanged for 10,000 old zlotych and 1 US$ exchange rate was ca. 2.5 zlotych (new).

Republika Srpska

Republika Srpska was a breakaway region of Bosnia. As with Krajina, it pegged its currency, the

Republika Srpska dinar, to that of Yugoslavia. Their bills were almost the same as Krajina’s, but they issued fewer and did not issue currency after 1993.

Romania

Romania experienced hyperinflation in the 1990s. The highest denomination in 1990 was 100

lei and in 1998 was 100,000 lei. By 2000 it was 500,000 lei. In early 2005 it was 1,000,000 lei. In July 2005 the leu was replaced by the new leu at 10,000 old lei = 1 new leu. Inflation in 2005 was 9%.

[2] In July 2005 the highest denomination became 500 lei (= 5,000,000 old lei).

Soviet Union / Russian Federation

Between 1921 and 1922, inflation in the

Soviet Union reached 213%.

In 1992, the first year of post-

Soviet economic reform, inflation was 2,520%. In 1993, the annual rate was 840%, and in 1994, 224%. The ruble devalued from about 40 r/$ in 1991 to about 5,000 r/$ in late 1997. In 1998, a denominated ruble was introduced at the exchange rate of 1 new ruble = 1,000 pre-1998 rubles. In the second half of the same year, ruble fell to about 30 r/$ as a result of

financial crisis.

Taiwan

As the

Chinese Civil War reached its peak, Taiwan also suffered from the hyperinflation that has ravaged China in late 1940s. Highest denomination issued was a 1,000,000

Dollar Bearer’s Cheque. Inflation was finally brought under control at introduction of New Taiwan Dollar in 15 June 1949 at rate of 40,000 old Dollar = 1 New Dollar

A 100,000

Ukrainian karbovantsi(used between 1992 and 1996). In 1996, it was taken out of circulation, and was replaced by the Hryvnya at an exchange rate of 100,000 karbovantsi = 1

Hryvnya (approx. USD 0.50 at that time, about USD 0.20 as of 2007). This translates to an average inflation rate of approximately 1400% per month between 1992 and 1996

Ukraine

Ukraine experienced its worst inflation between 1993 and 1995. In 1992, the

Ukrainian karbovanetswas introduced, which was exchanged with the defunct

Soviet ruble at a rate of 1 UAK = 1 SUR. Before 1993, the highest denomination was 1,000 karbovantsiv. By 1995, it was 1,000,000 karbovantsiv. In 1996, during the transition to the

Hryvnya and the subsequent phase out of the karbovanets, the exchange rate was 100,000 UAK = 1 UAH. This translates to a hyperinflation rate of approximately 1,400% per month. By some estimates, inflation for the entire calendar year of 1993 was 10,000% or higher, with retail prices reaching over 100 times their pre-1993 level by the end of the year.

[29]

United States

During the

Revolutionary War, when the

Continental Congress authorized the printing of paper currency called

continental currency. The monthly inflation rate reached a peak of 47 percent in November 1779 (Bernholz 2003: 48). These notes depreciated rapidly, giving rise to the expression “not worth a continental.”

A second close encounter occurred during the

U.S. Civil War, between January 1861 and April 1865, the

Lerner Commodity Price Index of leading cities in the eastern Confederacy states increased from 100 to over 9,000.

[30] As the Civil War dragged on, the

Confederate dollar had less and less value, until it was almost worthless by the last few months of the war. Similarly, the Union government inflated its

greenbacks, with the monthly rate peaking at 40 percent in March 1864 (Bernholz 2003: 107).

[31]

Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia went through a period of hyperinflation and subsequent currency reforms from 1989–1994. The highest denomination in 1988 was 50,000

dinars. By 1989 it was 2,000,000 dinars. In the 1990 currency reform, 1 new dinar was exchanged for 10,000 old dinars. In the 1992 currency reform, 1 new dinar was exchanged for 10 old dinars. The highest denomination in 1992 was 50,000 dinars. By 1993, it was 10,000,000,000 dinars. In the 1993 currency reform, 1 new dinar was exchanged for 1,000,000 old dinars. However, before the year was over, the highest denomination was 500,000,000,000 dinars. In the 1994 currency reform, 1 new dinar was exchanged for 1,000,000,000 old dinars. In another currency reform a month later, 1 novi dinar was exchanged for 13 million dinars (1 novi dinar = 1

German mark at the time of exchange). The overall impact of hyperinflation: 1 novi dinar = 1 × 10

27~1.3 × 10

27 pre 1990 dinars.

Yugoslavia‘s rate of inflation hit 5 × 10

15 percent cumulative inflation over the time period 1 October 1993 and 24 January 1994.

Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo)

Zaire went through a period of inflation between 1989 and 1996. In 1988, the highest denomination was 5,000

zaires. By 1992, it was 5,000,000 zaires. In the 1993 currency reform, 1 nouveau zaire was exchanged for 3,000,000 old zaires. The highest denomination in 1996 was 1,000,000 nouveaux zaires. In 1997, Zaire was renamed the Congo Democratic Republic and changed its currency to francs. 1 franc was exchanged for 100,000 nouveaux zaires. One post-1997 franc was equivalent to 3 × 10

11 pre 1989 zaires.

Zimbabwe

The 100 trillion

Zimbabwean dollar banknote (10

14 dollars), equal to 10

27 pre-2006 dollars

Hyperinflation in Zimbabwe was one of the few instances that resulted in the abandonment of the local currency. At independence in 1980, the

Zimbabwe dollar (ZWD) was worth about USD 1.25. Afterwards, however, rampant inflation and the collapse of the economy severely devalued the currency. Inflation was steady before

Robert Mugabe in 1998 began a program of land reforms that primarily focused on taking land from white farmers and redistributing those properties and assets to black farmers, which sent food production and revenues from export of food plummeting.

[32][33][34] The result was that to pay its expenditures Mugabe’s government and

Gideon Gono’s

Reserve Bank printed more and more notes with higher face values.

Hyperinflation began early in the twenty-first century, reaching 624% in 2004. It fell back to low triple digits before surging to a new high of 1,730% in 2006. The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe revalued on 1 August 2006 at a ratio of 1 000 ZWD to each second dollar (ZWN), but year-to-year inflation rose by June 2007 to 11,000% (versus an earlier estimate of 9,000%). Larger denominations were progressively issued:

- 5 May: banknotes or “bearer cheques” for the value of ZWN 100 million and ZWN 250 million.[35]

- 15 May: new bearer cheques with a value of ZWN 500 million (then equivalent to about USD 2.50).[36]

- 20 May: a new series of notes (“agro cheques”) in denominations of $5 billion, $25 billion and $50 billion.

- 21 July: “agro cheque” for $100 billion.[37]

Inflation by 16 July officially surged to 2,200,000%

[38] with some analysts estimating figures surpassing 9,000,000 percent.

[39] As of 22 July 2008 the value of the ZWN fell to approximately 688 billion per 1 USD, or 688 trillion pre-August 2006 Zimbabwean dollars.

[40]

| Date ofredenomination | Currencycode | Value |

|---|

| 1 Aug 2006 | ZWN | 1 000 ZWD |

| 1 Aug 2008 | ZWR | 1010 ZWN= 1013 ZWD |

| 2 Feb 2009 | ZWL | 1012 ZWR= 1022 ZWN= 1025 ZWD |

On 1 August 2008, the Zimbabwe dollar was redenominated at the ratio of 10

10 ZWN to each third dollar (ZWR).

[41] On 19 August 2008, official figures announced for June estimated the inflation over 11,250,000%.

[42] Zimbabwe’s annual inflation was 231,000,000% in July

[43] (prices doubling every 17.3 days). For periods after July 2008, no official inflation statistics were released. Prof. Steve H. Hanke overcame the problem by estimating inflation rates after July 2008 and publishing the Hanke Hyperinflation Index for Zimbabwe.

[44] Prof. Hanke’s HHIZ measure indicated that the inflation peaked at an annual rate of 89.7 sextillion percent (89,700,000,000,000,000,000,000%) in mid-November 2008. The peak monthly rate was 79.6 billion percent, which is equivalent to a 98% daily rate, or around7× 10

108 percent yearly rate. At that rate, prices were doubling every 24.7 hours. Note that many of these figures should be considered mostly theoretic, since the hyperinflation did not proceed at that rate a whole year.

[45]

At its November 2008 peak, Zimbabwe’s rate of inflation approached, but failed to surpass, Hungary’s July 1946 world record.

[45] On 2 February 2009, the dollar was redenominated for the fourth time at the ratio of 10

12 ZWR to 1 ZWL, only three weeks after the $100 trillion banknote was issued on 16 January,

[46][47] but hyperinflation waned by then as official inflation rates in USD were announced and foreign transactions were legalised,

[45] and on 12 April the dollar was abandoned in favour of using only foreign currencies. The overall impact of hyperinflation was 1 ZWL = 10

25 ZWD.

[edit]Worst hyperinflations in world history

How to Turn 100 Trillion Dollars Into Five and Feel Good About It

The Highest-Denominated Bill Ever Issued Gives Value to Worthless Zimbabwe Currency

By PATRICK MCGROARTY And FARAI MUTSAKA

A 100-trillion-dollar bill, it turns out, is worth about $5.

Associated Press

A man in Harare, Zimbabwe, carried cash for groceries in 2008.

That’s the going rate for Zimbabwe’s highest denomination note, the biggest ever produced for legal tender—and a national symbol of monetary policy run amok. At one point in 2009, a hundred-trillion-dollar bill couldn’t buy a bus ticket in the capital of Harare.

But since then the value of the Zimbabwe dollar has soared. Not in Zimbabwe, where the currency has been abandoned, but on eBay.

The notes are a hot commodity among currency collectors and novelty buyers, fetching 15 times what they were officially worth in circulation. In the past decade, President Robert Mugabe and his allies attempted to prop up the economy—and their government—by printing money. Instead, the country’s central bankers sparked hyperinflation by issuing bills with more zeros.

The 100-trillion-dollar note, circulated for just a few months before the Zimbabwe dollar was officially abandoned as the country’s legal currency in 2009, marked the daily limit people were allowed to withdraw from their bank accounts. Prices rose, wreaking havoc.

The runaway inflation forced Zimbabweans to wait in line to buy bread, toothpaste and other essentials. They often carried bigger bags for their money than the few items they could afford with a devalued currency.

Today, all transactions are in foreign currencies, mainly the U.S. dollar and the South African rand. But Zimbabwe’s worthless bills are valuable—at least outside the country. That Zimbabwe’s currency happened to be denoted in dollars has amplified appeal, say currency dealers and collectors, particularly after the global financial crisis and mounting public debts sparked inflationary fears in the U.S.

SATURDAY, 22 JANUARY 2011

Posted by M.H. Forsyth

I’m reading

Wilt by Thomas Sharpe at the moment. It’s terribly good fun so far but I have been troubled, dear reader, sorely troubled by prices. Money is terribly important in

Wilt. The novel is all about class and budgets and careers. Henry Wilt himself earns £3,500 a year and his wife secretly spends seventy pounds on clothes and the starter in a restaurant costs 95p.

Trouble is, I’ve no idea what that means in today’s green and folding. It’s only thirty-five years since Wilt was published, but inflation is such that I can make neither tail nor head of these (terribly important) details.

I get the same thing reading Pride and Prejudice. People are always described as having an income of so many hundred or thousand a year, and the girls go wild (or don’t); but the modern reader is left scratching his head and furrowing his brow and wondering whether to go down to the library with a slide-rule and work everything out in compound inflation.

Nevermore, dear calculating reader, nevermore. Use this:

It’s so damned handy that I’ve installed it as a permanent widget on the right of the blog. I’m afraid that I couldn’t find one that would go straight to dollars and all those other funny foreign currencies that don’t have a picture of the Queen on them and are therefore worthless. But if you’re American (are you, dear reader? I’d so like to know), you can continue on to

a site like this and find out that Mr Darcy’s £10,000 a year in 1813 is:

£520,000 in modern Britain

$831,869.95 in the USA

$827,134.49 in Canada

$841,250.62 Down Under

€612,635.63 in those amusing countries beyond the English Channel

And the rest of you can work it out for yourselves. The general point is that Mr Darcy is even richer than I am, and it’s no surprise that Miss Bennett fell in love with him.

The Inky Fool returns from the cash point

01.04

01.04

Unknown

Unknown